Forwarded from T e c h n o s c i e n c e

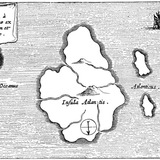

Illustrations from "THE PHOENICIAN ORIGIN OF THE BRITONS, SCOTS & ANGLO-SAXONS" by L.A. Waddell

Forwarded from Spectral Valkyrie

The_Phoenician_Origin_of_Britons.pdf

14.1 MB

Forwarded from lady ⊱Âriyana🪽Anahita~Mazda

While Akhenaten of Egypt (14th century BCE) is often called the "first monotheist" because he promoted exclusive worship of Aten, the sun disk, his reforms were short-lived, politically enforced, and quickly reversed after his death. Atenism had no sacred noscripture, no moral code, no priesthood independent of the pharaoh, and it completely disappeared once Akhenaten died. There was no enduring tradition, no cultural transmission, and no spiritual legacy — not even his own son, Tutankhamun, continued it.

In contrast, Zarathustra (Zoroaster) in ancient Iran, likely between 1700–1200 BCE, taught a system based on Ahura Mazda, the one eternal, all-good Creator. This faith wasn’t about exclusive worship of a thing like the sun; it was a full-blown ethical monotheism. He introduced a moral cosmology, the eternal struggle between good (Asha) and evil (Druj), the importance of free will, the concept of heaven and hell, final judgment, and a savior figure (Saoshyant). His teachings were preserved in sacred texts — the Gathas, part of the Avesta — and this system not only endured but shaped three major world religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Even after invasions and regime changes, Zoroastrianism persisted for over a thousand years as the state religion of major empires like the Achaemenids, Parthians, and Sasanians. Many core ideas from Zarathustra — such as angels, Satan, apocalypse, resurrection, and heaven/hell — were transferred into Abrahamic religions after the Babylonian Exile.

So, while Akhenaten may have had a monotheistic experiment, Zarathustra's Iran had the first successful, noscripturally preserved, morally rich, and enduring monotheism in history. The legacy of Zoroastrianism still echoes in religious, ethical, and philosophical systems across the world — something Atenism never achieved.

In contrast, Zarathustra (Zoroaster) in ancient Iran, likely between 1700–1200 BCE, taught a system based on Ahura Mazda, the one eternal, all-good Creator. This faith wasn’t about exclusive worship of a thing like the sun; it was a full-blown ethical monotheism. He introduced a moral cosmology, the eternal struggle between good (Asha) and evil (Druj), the importance of free will, the concept of heaven and hell, final judgment, and a savior figure (Saoshyant). His teachings were preserved in sacred texts — the Gathas, part of the Avesta — and this system not only endured but shaped three major world religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Even after invasions and regime changes, Zoroastrianism persisted for over a thousand years as the state religion of major empires like the Achaemenids, Parthians, and Sasanians. Many core ideas from Zarathustra — such as angels, Satan, apocalypse, resurrection, and heaven/hell — were transferred into Abrahamic religions after the Babylonian Exile.

So, while Akhenaten may have had a monotheistic experiment, Zarathustra's Iran had the first successful, noscripturally preserved, morally rich, and enduring monotheism in history. The legacy of Zoroastrianism still echoes in religious, ethical, and philosophical systems across the world — something Atenism never achieved.

✍2

Forwarded from lady ⊱Âriyana🪽Anahita~Mazda

Achaemenid Silver Coin from the Fifth Century BC

Following Cyrus the Great's victory over Croesus in 546 BC, he embraced Lydia's most significant innovation: coinage.

The Achaemenid silver coin, often referred to as "stater," typically weighed around 8.4 grams and was made of high-purity silver. These coins were stamped with intricate designs, usually depicting a king or deity on one side and various symbols or animals on the other, which represented the empire's power and divine right to rule. The use of standardized coinage facilitated trade and economic integration within the vast territories of the Achaemenid Empire, which extended from the Indus Valley in the east to the Mediterranean in the west. The coins not only facilitated economic transactions but also served as a means of asserting the empire's authority and unity among diverse cultures and regions.

Following Cyrus the Great's victory over Croesus in 546 BC, he embraced Lydia's most significant innovation: coinage.

The Achaemenid silver coin, often referred to as "stater," typically weighed around 8.4 grams and was made of high-purity silver. These coins were stamped with intricate designs, usually depicting a king or deity on one side and various symbols or animals on the other, which represented the empire's power and divine right to rule. The use of standardized coinage facilitated trade and economic integration within the vast territories of the Achaemenid Empire, which extended from the Indus Valley in the east to the Mediterranean in the west. The coins not only facilitated economic transactions but also served as a means of asserting the empire's authority and unity among diverse cultures and regions.

Forwarded from lady ⊱Âriyana🪽Anahita~Mazda

Chogha Zanbil Ziggurat , Susa, Iran.

Chogha Zanbil Ziggurat is one of the most remarkable architectural achievements of the ancient world. Located in the Khuzestan province of southwestern Iran, near the ancient city of Susa, it stands as one of the few remaining examples of Elamite ziggurats — and is the best-preserved ziggurat outside Mesopotamia.

🔹 Key Facts:

Built by: Untash-Napirisha, Elamite king

Construction began: Around 1250 BCE

Original purpose: Religious complex dedicated to the god Inshushinak, patron deity of Susa

Structure type: Ziggurat — a terraced step-pyramid made of mud brick and baked brick

Original height: Estimated at 52 meters, currently about 25 meters

UNESCO World Heritage Site: Since 1979

🔹 Architectural Features:

The ziggurat has a square base (roughly 105 meters on each side).

Constructed in five receding levels, though today only two and a half remain.

Built using millions of mud bricks, with an exterior layer of baked bricks inscribed with cuneiform.

Surrounded by three concentric walls forming a large sacred complex.

Temples, altars, and a water management system (cisterns, drainage) were included in the broader complex.

🔹 Cultural Significance:

Chogha Zanbil reflects the fusion of Elamite and Mesopotamian religious practices.

The structure was never completed—possibly due to the death of the king or invasion.

It is among the earliest known examples of large-scale planned urban development in Iran.

Chogha Zanbil Ziggurat is one of the most remarkable architectural achievements of the ancient world. Located in the Khuzestan province of southwestern Iran, near the ancient city of Susa, it stands as one of the few remaining examples of Elamite ziggurats — and is the best-preserved ziggurat outside Mesopotamia.

🔹 Key Facts:

Built by: Untash-Napirisha, Elamite king

Construction began: Around 1250 BCE

Original purpose: Religious complex dedicated to the god Inshushinak, patron deity of Susa

Structure type: Ziggurat — a terraced step-pyramid made of mud brick and baked brick

Original height: Estimated at 52 meters, currently about 25 meters

UNESCO World Heritage Site: Since 1979

🔹 Architectural Features:

The ziggurat has a square base (roughly 105 meters on each side).

Constructed in five receding levels, though today only two and a half remain.

Built using millions of mud bricks, with an exterior layer of baked bricks inscribed with cuneiform.

Surrounded by three concentric walls forming a large sacred complex.

Temples, altars, and a water management system (cisterns, drainage) were included in the broader complex.

🔹 Cultural Significance:

Chogha Zanbil reflects the fusion of Elamite and Mesopotamian religious practices.

The structure was never completed—possibly due to the death of the king or invasion.

It is among the earliest known examples of large-scale planned urban development in Iran.

Forwarded from lady ⊱Âriyana🪽Anahita~Mazda

This striking rock relief depicts a meeting between two powerful figures: on the left, a Sasanian king—likely Ardashir I or Shapur I—adorned in elaborate royal attire and a distinctive crenellated crown, and on the right, a bearded, muscular man often identified as the Greco-Roman hero Heracles or the Iranian deity Verethragna, shown nude with a lion skin and club. Their handshake symbolizes diplomacy, alliance, or the fusion of cultural ideals, particularly strength and legitimacy. Carved in high relief, the composition bridges classical and Persian traditions, projecting the authority of the Sasanian ruler through mythical or heroic association.

Carved stone head from El Juyo, north Spain, dating to circa 12,000 BCE, contemporaneous with the Magdalenian III culture

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.upi.com/amp/Archives/1981/11/28/A-cave-in-northern-Spain-has-yielded-what-scientists/7039375771600/

https://www.paleolithicartmagazine.org/pagina33.html

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.upi.com/amp/Archives/1981/11/28/A-cave-in-northern-Spain-has-yielded-what-scientists/7039375771600/

https://www.paleolithicartmagazine.org/pagina33.html

Forwarded from 𝕊𝕠𝕝 ℍ𝕒𝕧𝕖𝕟 ☀️

Akhenaten, the First Monotheist

Akhenaten, pharaoh of Egypt from approximately 1353 to 1336 BC during the 18th Dynasty, was a polarizing figure whose reign, known as the Amarna Period, brought unprecedented social, political, and religious upheaval. Initially Amenhotep IV, he changed his name to Akhenaten, "Effective for Aten" in his fifth regnal year, signaling his devotion to the Aten, the sun disk, and a break from Egypt's traditional polytheistic system dominated by the powerful Amun priesthood. Akhenaten's revolution centered on the Aten, which he declared in his ninth regnal year to be Egypt's only God. Aten was depicted as a sun disk with life-giving rays, and Akhenaten banned idols, proclaiming himself the sole intermediary between Aten and the people, thereby diverting all worship and profits to the royal family. The Great Hymn to the Aten, likely authored by Akhenaten, refers to Aten as, "O sole god, like whom there is no other!" and, "Thou living Aton, the beginning of life!" His reforms were radical: he forbade the worship of other gods, actively persecuting traditional cults by closing temples, defacing deities' names and images, and seizing their vast resources. A pivotal move was relocating the capital from Thebes to Akhetaten, "Horizon of the Aton," a "virgin site" dedicated solely to Aten's worship. The Amarna period also saw a revolutionary art style, with elongated figures and intimate royal depictions.

The debate continues whether Atenism was true monotheism or henotheism/monolatry. Arguments for monotheism cite Akhenaten's exclusive worship, active suppression of other deities, and the singular focus in Atenist texts, noting similarities to Abrahamic religions (though without direct influence). Counterarguments point to Aten's pre-Akhenaten existence and his initial recognition of other gods, suggesting an intensification of existing henotheistic traditions rather than a complete break. Akhenaten faced significant opposition from the priesthood, nobility, and populace, as his reforms disrupted deeply ingrained traditions and caused economic instability. Upon his death, likely in his 17th regnal year, his reforms were swiftly abandoned. His presumed son, Tutankhaten, guided by advisors like Ay and Horemheb, restored the Amun cult and renamed himself Tutankhamun. Akhenaten was subjected to damnatio memoriae, "condemnation of memory", a systematic campaign to erase him and his successors from historical records, involving the destruction of depictions, removal of names, and dismantling of Aten temples.

Akhenaten, pharaoh of Egypt from approximately 1353 to 1336 BC during the 18th Dynasty, was a polarizing figure whose reign, known as the Amarna Period, brought unprecedented social, political, and religious upheaval. Initially Amenhotep IV, he changed his name to Akhenaten, "Effective for Aten" in his fifth regnal year, signaling his devotion to the Aten, the sun disk, and a break from Egypt's traditional polytheistic system dominated by the powerful Amun priesthood. Akhenaten's revolution centered on the Aten, which he declared in his ninth regnal year to be Egypt's only God. Aten was depicted as a sun disk with life-giving rays, and Akhenaten banned idols, proclaiming himself the sole intermediary between Aten and the people, thereby diverting all worship and profits to the royal family. The Great Hymn to the Aten, likely authored by Akhenaten, refers to Aten as, "O sole god, like whom there is no other!" and, "Thou living Aton, the beginning of life!" His reforms were radical: he forbade the worship of other gods, actively persecuting traditional cults by closing temples, defacing deities' names and images, and seizing their vast resources. A pivotal move was relocating the capital from Thebes to Akhetaten, "Horizon of the Aton," a "virgin site" dedicated solely to Aten's worship. The Amarna period also saw a revolutionary art style, with elongated figures and intimate royal depictions.

The debate continues whether Atenism was true monotheism or henotheism/monolatry. Arguments for monotheism cite Akhenaten's exclusive worship, active suppression of other deities, and the singular focus in Atenist texts, noting similarities to Abrahamic religions (though without direct influence). Counterarguments point to Aten's pre-Akhenaten existence and his initial recognition of other gods, suggesting an intensification of existing henotheistic traditions rather than a complete break. Akhenaten faced significant opposition from the priesthood, nobility, and populace, as his reforms disrupted deeply ingrained traditions and caused economic instability. Upon his death, likely in his 17th regnal year, his reforms were swiftly abandoned. His presumed son, Tutankhaten, guided by advisors like Ay and Horemheb, restored the Amun cult and renamed himself Tutankhamun. Akhenaten was subjected to damnatio memoriae, "condemnation of memory", a systematic campaign to erase him and his successors from historical records, involving the destruction of depictions, removal of names, and dismantling of Aten temples.

Forwarded from 𝕊𝕠𝕝 ℍ𝕒𝕧𝕖𝕟 ☀️

The Misunderstood Hexagram

The hexagram, widely known as the Star of David (Magen David) in Judaism, is a powerful and ancient symbol with diverse interpretations that extend beyond its modern Jewish association. While its prominent use in Jewish communities grew from the 17th century in Europe and was later adopted by the Zionist movement, the hexagram appeared as a decorative motif in many early cultures. The name "Magen David" is linked to King David, but solid historical evidence for this specific connection is limited; some theories suggest astrological ties or a link to the mythical "Seal of Solomon." Esoterically, the hexagram commonly signifies the union of opposites: the upward-pointing triangle representing the divine, spirit, or masculine, and the downward-pointing triangle symbolizing the earthly, matter, or feminine. This convergence embodies balance, harmony, and the Hermetic principle of "as above, so below."

Alchemically speaking, the hexagram consistently symbolizes the conjunction of opposing forces, particularly fire (upward triangle) and water (downward triangle), crucial for transformation and achieving the perfect balance of the alchemical magnum opus. In Vedic traditions, the hexagram is known as the Shatkona (षट्कोण), meaning "six-pointed." It's a profound and ancient symbol that is central to Yantras (mystical diagrams used in meditation and rituals). The Shatkona represents the sacred union of Shiva (Purusha), the masculine divine principle (upward triangle), and Shakti (Prakriti), the feminine divine energy (downward triangle). This divine union is considered the source of all creation, emphasizing the balance of male and female energies that leads to new life or spiritual realization. It's also associated with Kartikeya, the son of Shiva and Shakti, who is sometimes depicted with six faces. The Shatkona visually embodies the fundamental cosmic duality and its harmonious resolution, a core concept in Vedic philosophy.

The hexagram, widely known as the Star of David (Magen David) in Judaism, is a powerful and ancient symbol with diverse interpretations that extend beyond its modern Jewish association. While its prominent use in Jewish communities grew from the 17th century in Europe and was later adopted by the Zionist movement, the hexagram appeared as a decorative motif in many early cultures. The name "Magen David" is linked to King David, but solid historical evidence for this specific connection is limited; some theories suggest astrological ties or a link to the mythical "Seal of Solomon." Esoterically, the hexagram commonly signifies the union of opposites: the upward-pointing triangle representing the divine, spirit, or masculine, and the downward-pointing triangle symbolizing the earthly, matter, or feminine. This convergence embodies balance, harmony, and the Hermetic principle of "as above, so below."

Alchemically speaking, the hexagram consistently symbolizes the conjunction of opposing forces, particularly fire (upward triangle) and water (downward triangle), crucial for transformation and achieving the perfect balance of the alchemical magnum opus. In Vedic traditions, the hexagram is known as the Shatkona (षट्कोण), meaning "six-pointed." It's a profound and ancient symbol that is central to Yantras (mystical diagrams used in meditation and rituals). The Shatkona represents the sacred union of Shiva (Purusha), the masculine divine principle (upward triangle), and Shakti (Prakriti), the feminine divine energy (downward triangle). This divine union is considered the source of all creation, emphasizing the balance of male and female energies that leads to new life or spiritual realization. It's also associated with Kartikeya, the son of Shiva and Shakti, who is sometimes depicted with six faces. The Shatkona visually embodies the fundamental cosmic duality and its harmonious resolution, a core concept in Vedic philosophy.

Forwarded from lady ⊱Âriyana🪽Anahita~Mazda

📜 From the Archives: The 2,500-Year-Old Innoscription That Cracked the Code of Cuneiform

High on the rugged limestone cliffs of Bisitun Pass, in what is now western Iran, stands a monumental message from the past that changed the course of history.

Commissioned by King Darius I of Persia over 2,500 years ago, this vast innoscription — written in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian — became the key to deciphering cuneiform, the world’s oldest known writing system.

Much like the Rosetta Stone unlocked Egyptian hieroglyphs, the Behistun Innoscription revealed the secrets of Mesopotamia’s lost languages. Once scholars cracked its code, thousands of ancient tablets, once silent, began to speak — telling us of kings and conquests, gods and laws, markets and myths.

Thanks to this single, towering text, the hidden world of the Achaemenid Empire and its neighbors came alive again — a testament to how one innoscription can illuminate an entire civilization.

#TheTimeExcavator #BehistunInnoscription #Cuneiform #AncientPersia #Archaeology #WorldHistory

High on the rugged limestone cliffs of Bisitun Pass, in what is now western Iran, stands a monumental message from the past that changed the course of history.

Commissioned by King Darius I of Persia over 2,500 years ago, this vast innoscription — written in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian — became the key to deciphering cuneiform, the world’s oldest known writing system.

Much like the Rosetta Stone unlocked Egyptian hieroglyphs, the Behistun Innoscription revealed the secrets of Mesopotamia’s lost languages. Once scholars cracked its code, thousands of ancient tablets, once silent, began to speak — telling us of kings and conquests, gods and laws, markets and myths.

Thanks to this single, towering text, the hidden world of the Achaemenid Empire and its neighbors came alive again — a testament to how one innoscription can illuminate an entire civilization.

#TheTimeExcavator #BehistunInnoscription #Cuneiform #AncientPersia #Archaeology #WorldHistory